By Shirley Dusinberre Durham, October 2010

|

| G. H. Underwood and I at Verulam |

When the war was over and the British soldiers had left their practice battleground on Royal Ashdown fairways, golf resumed for the Toffs and the Cantelupe. Royal Ashdown members played at the shank of the day, while the Artisans enjoyed the rest of the long summer's light. Sometimes the two clubs, Cantelupe and Royal Ashdown, competed in a friendly, but serious, rivalry. My English friend George Underwood, twice Captain of the Cantelupe Golf Club, told me that because the Artisans were not permitted to enjoy the inside of the clubhouse, a serving window to the golf course was built off the men's bar, so that foursomes could drink together during their matches. He believed it to be the only window of its kind in England.

Underwood is Abe Mitchell's nephew, son of Abe's sister Mabel Seymour. George, who once "played off single figures" (in handicap-speak), holds the painful memory of losing several golf clubs from a small set made for him by his Uncle Abe in 1928. In WWII, George served in the Royal Navy. He was aboard when HMS Dido was torpedoed off the island of Crete. Men were lost but the damaged ship made the long voyage to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for repairs, giving the young Navy man a summer in New York City he will never forget. George shared everything with me, including something I've just decided not to share with you, although you may find it in my book.

THE RYDER CUP EVOLVES

There is no question that until the early 1920s, British professionals were the best golfers anywhere. Vardon, Taylor and Braid, et al. traveled the world, winning their Opens as well as ours. But that changed after American-born Walter Hagen popularized an American presence in the Open by winning it in 1922, 1924, 1928 and 1929.Hagen never played as an amateur. He permanently lost his amateur status when he caddied at age fourteen. He won the US Open in 1914 and 1919, while he was the pro at the Country Club of Rochester. He never smoked or drank until he was 25, and after that, it was more an act than an actuality. He left Rochester to become pro at the new Oakland Hills Club in Detroit, where he and his new wife enjoyed clubhouse privileges.

Then, abruptly, Walter decided to work for himself. He hired a business agent and a press secretary, quit Oakland Hills and reinvented golf, becoming the first pro to successfully earn his living by playing competitive golf and exhibitions. After he won the 1919 US Open, he accepted his first invitation to play abroad, in the 1920 Open, at Deal, on the south coast of England. The English social order and sporting scene would never be the same. The Ryder Cup Story would begin.

Hagen, George Duncan and Abe Mitchell made headlines at that 1920 Open -- Hagen, because he changed his shoes in a chauffeured Austin-Daimler and scored so badly, Mitchell, (British Match Play Champion), because he led the field by thirteen strokes at one point, and Duncan, because he won. The following week Hagen and his two new friends, Mitchell and Duncan, went off to the French Open in Paris, which Hagen won and Mitchell and Duncan were second and third. I surmise it was about then that Hagen talked them into touring the United States, if Hagen could find them a sponsor, perhaps merchandizer Rodman Wanamaker, who had orchestrated the founding of the PGA of America in 1916.

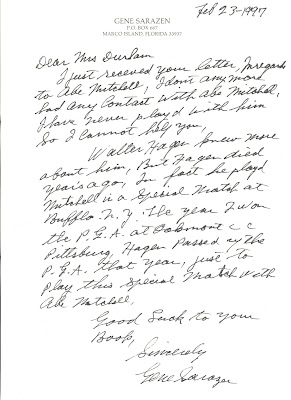

Until I received Gene Sarazen's letter (right), I had no idea that Abe Mitchell had ever set foot in the United States before the 1931 Ryder Cup in Ohio. The letter reshaped my view about the origins of the Ryder Cup. I went to the library to see if our newspapers ever wrote about the Mitchell and Duncan tours.

The tidbit in Sarazen's letter was, of course, that Hagen, as PGA champion in 1921, did not defend his title. In 1922, he skipped the PGA Championship (match play until 1957), the event for which he would become famous for winning the most of -- 1921, '24-'27, which adds up to five times. Hagen chose instead to make more money in less time by playing with his two British pals, Abe and George, in the two-day Western New York Open Championship in Buffalo.

Duncan's and Mitchell's success in America, in conjunction with Hagen's showmanship, surely contributed to a future for international competition. The British pros would take the message home, where it would become a mission to which Sam Ryder would put his hand.

No comments:

Post a Comment